Youth and Age at Amenia

I was the great Jew, Benjamin Disraeli, who said: “Youth is a blunder; manhood a struggle; old age a regret.” And so with blunder and regret and perhaps something of struggle, we came together last month in the second Amenia Conference.

The first conference at Joel Spingarn’s beautiful country estate, took place in 1916. And after its few days of frank fellowship there was no adequate reason left for essential differences of opinion between the followers of Booker T. Washington, then just dead, and those younger men who had so vigorously opposed some of his policies.

The second Amenia conference held at Troutbeck, seventeen years later, had a definite object,—one much more usual in this world, and yet emphasized today both within and without the Negro race because of World War and unemployment. It was an attempt to bring together and into sympathetic understanding, Youth and Age interested in the Negro problem. And more particularly Youth, with a fringe of Age; and not extreme youth. Eliminating four admittedly among the elders, the others ranged in age between twenty-five and thirty-five, with a median age of thirty, that is, they were well out of college and started on their life work, and yet, as the invitations suggested, they were still with inquiring minds and still unsettled as to their main life work.

These younger conferees may be classed in various ways:

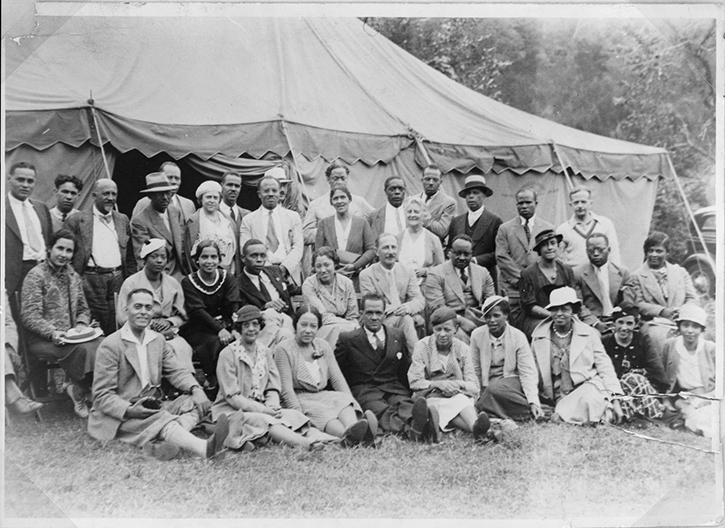

Participants in the 1933 Amenia Conference.

Participants in the 1933 Amenia Conference.

Third Row (left to right): Ralph Bunche, Edward P. Lovett, W.E.B. Du Bois, Abram Harris, Charles Houston, Grace Nail Johnson, Roy Wilkins, E. Franklin Frazier, Sterling Brown, Lillian Alexander, Emmett Dorsey, William Pickens, Mary White Ovington, Ira De A. Reid, James Weldon Johnson, and Walter White. Second Row (left to right): Hope Spingarn, Hazel Brown, Juanita Jackson, M. Moran Weston, Wenonah Logan, Joel Spingarn, Elmer A. Carter, Mabel J. Bryde, Frank Wilson, and Marion Cuthbert. Front Row (left to right): Dr. Ernest Alexander, Ruth McGee, Dr. Virginia Alexander, Howard Shaw, Anna Arnold, Sara E. Reid, Pauline Young, Frances Williams, unidentified. Source:Library of Congress

There were 5 social workers; 5 college professors, 4 Y.W.C.A. workers, 3 teachers, 3 lawyers, 2 artisans, 2 librarians, a physician, a student and a Y.M.C.A. worker.

Representing age (more or less willingly), were 2 editors, a professor and a social worker. All were college graduates except one. There were two Doctors of Philosophy.

Among the visitors were a distinguished author, a Federal official, a social worker and a physician.

This, of course, was far from being a cross-section of the group represented. Those present were picked almost haphazard from a list of over 400 names sent to us from all parts of the country. The younger people were, however, very interesting. Among them 3 gave evidence of first-class scholarship, based on thoughtful study and reading; ten were clear-thinkers, able to state their thoughts succinctly and definitely, not at all settled in thought or opinion and frankly aware of the fact, and yet able to contribute to thought. Four were more emotional, not altogether clear in thought, but evidently in earnest and groping. Two were bright but cynical, and the rest were a miscellaneous group, some of whom lacked training and others were merely silent.

On the whole, they were inspiring. They had evidently been thinking and they had not stopped the process. Their difficulty was mainly the difficulty of all youth. Inspired and swept on by its vision, it does not know or rightly interpret the past and is apt to be too hurried carefully to study the present. For instance, one earnest young man told of the need of a Negro lobby in Washington and how certain persons were going to start one. The officials of the N.A.A.C.P. promptly told of the lobby which had been sustained there for five or more years; and the real solution of this apparent contradiction was: How efficient was the former lobby? Why was it not continued? And how far was the present proposal learning from the mistakes and successes of the first venture?

Only by such linking of past, present and future can real national and group advance be made, and this, I think, the Amenia conference was conscious of before it adjourned.

Of course, the difficulty with age and youth is to find a common language; an attitude in which they can approach each other. It is hard for age to admit or understand that it has not thought of everything or attempted everything, or done what it has done as efficiently as it might have done. It is equally difficult for youth to know that age has thought of some of the various problems which bother youth; has tried and failed and succeeded and for reasons not explained altogether by either stupidity or cowardice. In attitude, youth with its tongue in its cheek assumes very often a silent reverence for age which it does not in the slightest feel. And age recognizes the mockery, and on the other hand, it is exceedingly difficult for age not to patronize youth, and to say by silences and inflections: “You really know very little.” Which is of course true but applies but little more to youth than to age.

We talked from Friday to Monday, interspersed with swimming and glorious food. Our general thesis was:

In view of the present world depression and the race problems which have exhibited themselves in Germany, India and Africa, the West Indies and the United States, what should be the ultimate goal of a young, educated American Negro with regard to:

A. Occupation and Income

B. Racial Organization

C. Inter-Racial Co-operation

As a matter of fact most of the discussion confined itself to the economic conditions and the influence of education and politics on these conditions, There was little time left for the matter of racial organization, while the interracial aspects of the problem received practically no attention.

The discussion was interesting. There was not a single speech made; that is, there was no attempt at rounded periods and eloquence by persons who had nothing in particular to say. No one even attempted it. When anyone got the floor, they really took hold of the thought and did something with it. And in the end, the general consensus of agreement was rather startling. Far greater than most of us had thought. These were the resolutions:

This conference was called to make a critical appraisal of the Negro’s existing situation in American Society and to consider underlying principles for future action. Such criticism at this stage does not involve the offering of concrete program for any organization for administrative guidance.

There has been no attempt to disparage the older type of leadership. We appreciate their importance and contributions but we feel that in a period in which economic, political, and social values are rapidly shifting, and the very structure of organized society is being revamped, the leadership which is necessary is that which will integrate the special problems of the Negro within the larger issues facing the nation.

The primary problem is economic. Individual ownership expressing itself through the control and exploitation of natural resources and industrial machinery has failed in the past to equalize consumption with production.

As a result of which the whole system of private property and private profit is being called into question. The government is being forced to attempt an economic reorganization based upon a “co-partnership” between capital, labor and government itself. The government is attempting to augment consumptive power by increasing wages, shortening hours and controlling the labor and commodity markets. As a consumer the Negro has always had a low purchasing power as a result of his low wages coming from his inferior and restricted position in the labor market. If the government program fails to make full and equal provision for the Negro, it cannot be effective in restoring economic stability.

In the past there has been a greater exploitation of Negro labor than of any other section of the working class, manifesting itself particularly in lower wages, longer hours, excessive use of child labor and a higher proportion of women at work. Heretofore there has been slight recognition by Negro labor or Negro leaders of the significance of this exploitation in the economic order. Consequently no technique or philosophy has been developed to change the historic status of Negro labor. Hence in the present governmental set-up there is grave danger that this historic status will be perpetuated. As a result the lower wages on the one hand will reduce the purchasing power of Negro labor and on the other be a constant threat to the standards and security of white labor.

The question then arises how far existing agencies working among and for Negroes are theoretically and structurally prepared to cope with this situation. It is the opinion of the conference that the welfare of white and black labor are one and inseparable and that the existing agencies working among and for Negroes have conspicuously failed in facing a necessary alignment between black and white labor.

It is impossible to make any permanent improvement in the status and the security of white labor without making an identical improvement in the status and the security of Negro labor.

The Negro worker must be made conscious of his relation to white labor and the white worker must be made conscious that the purposes of labor, immediate or ultimate cannot be achieved, without full participation by the Negro worker.

The traditional labor movement as based upon craft autonomy and separatism which is non-political in outlook and centering its attention upon the control of jobs and wages for the minority of skilled white workers is an ineffective agency for aligning white and black labor for the larger labor objectives.

These objectives can only be attained through a new labor movement. This movement must direct its immediate attention to the organizing of the great mass of workers both skilled and unskilled, white and black. Its activities must be political as well as economic for the purpose of effecting such social legislation as old age pensions, unemployment insurance, child and female labor, etc. These social reforms may go to the extent of change in the form of Government itself. The Conference sees three possibilities:

- Fascism

- Communism

- Reformed Democracy.

The conference is opposed to Fascism because it would crystalize the Negro’s position at the bottom of the social structure. Communism is impossible without a fundamental transformation in the psychology and the attitude of white workers on the race question and a change in the Negro’s conception of himself as a worker. A democracy that is attempting to reform itself is a fact which has to be reckoned with. In the process of reform the interests of the Negro cannot be adequately safeguarded by white paternalism in government. It is absolutely indispensable that in this attempt of the government to control agriculture and industry, there be adequate Negro representations on all boards and fields staffs.

While the accomplishment of these aims cannot be achieved except through the cooperation of white and black, the primary responsibility for the initiation development and execution of this program rests upon the Negro himself. This is predicated upon the increased economic independence of the Negro. No matter what artificial class difference may seem to exist within the Negro group it must be recognized that all elements of the Race must weld themselves together for the common welfare. This point of view must be indoctrinated through the churches, educational institutions and other agencies working in behalf of the Negro. The first steps toward the rapprochement between the educated Negro and the Negro mass must be taken by the educated Negro himself. The Finding Committee recommends that the practical implications of this program be referred to a committee on continuation to be appointed at this conference.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There were some little sidelights that are of interest First and foremost, I discovered that these young people could not sing. It was astonishing. It would be impossible to get thirty young Germans, Frenchmen, Spaniards, Haitians or Chinese together, who could not and would not sing enthusiastically songs that they all knew. But we did not know any songs and we could not sing them. We could not even try. We were too sophisticated. We had heard Hayes and Marian Anderson, not to mention the Metropolitan Opera, and we were dumb in both senses of the word.

In addition to that there was on the part of a few a certain, not unexpected, but nevertheless startling lack of self-discipline. It has always been interesting to me to see how young people in many countries organized their government and discipline and enforce it with a certain ruthlessness. But here out of twenty-six, five did as they pleased with regard to noise, sleep and enjoyment with utter disregard of the perfectly evident desires of the rest, and to cap the climax, the rest uttered no protest. I have seen evidence of this sort of thing among young colored people elsewhere. It is for us and the race a new and pressing problem.

Perhaps the second Amenia conference will not be as epoch-making as the first, but on the other hand, it is just as possible that it will be more significant for the future than any conference which colored people have yet held, That depends entirely upon what reactions follow this meeting.

This sketch of the conference cannot close without reference to the hospitality of the host, Joel E. Spingarn, and the thoughtful co-operation of his wife, his two daughters and his two sons. It was withal a very beautiful experience.