Tulsa Riots

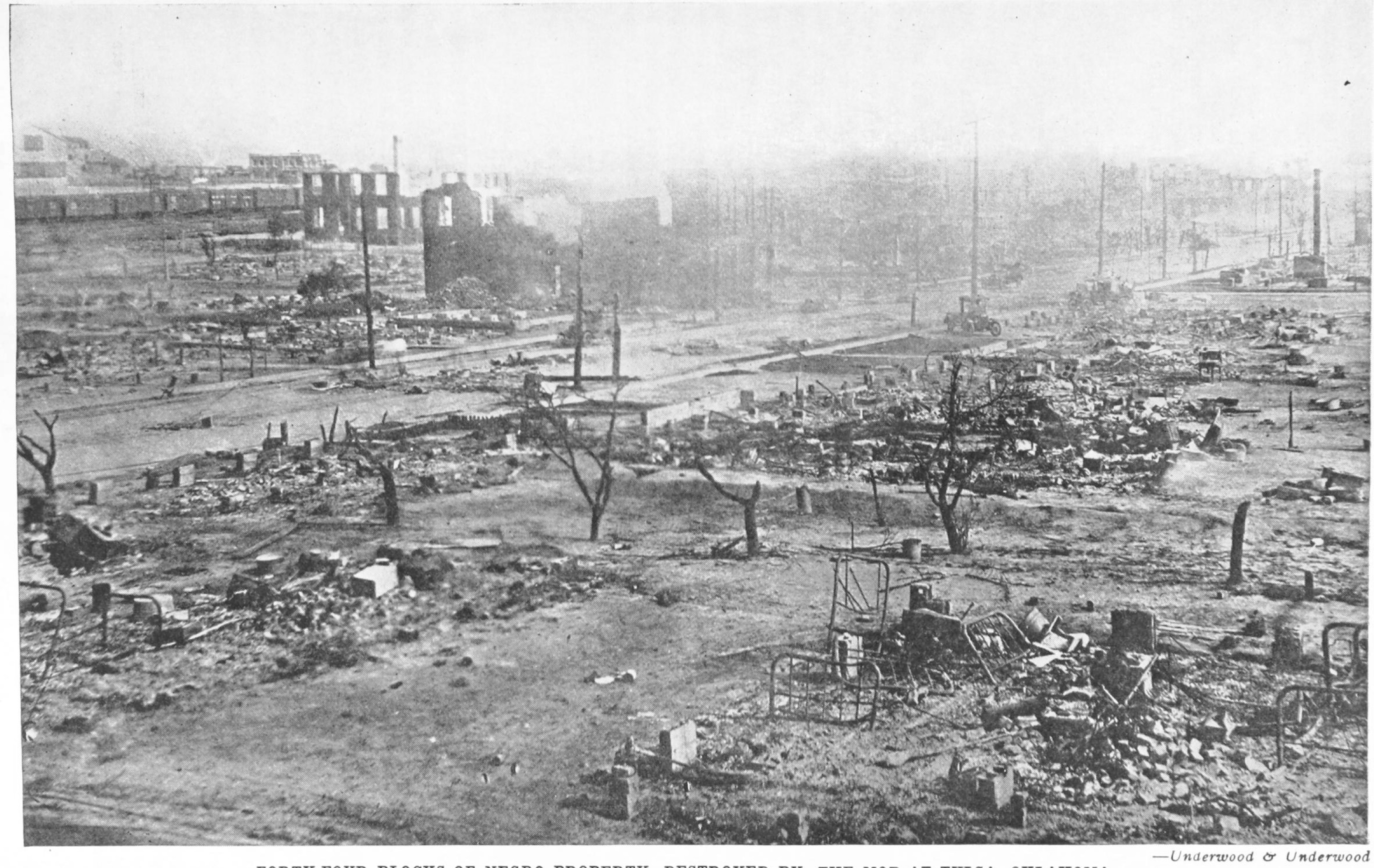

Within six hours of the time, on June 1, when the New York Evening Post called up the National Office on the telephone to ask whether anything had been heard of race trouble in Tulsa, Okla., a representative was on the way to the battle-scarred city to investigate for the Association. Meanwhile reports continued to come in which showed that one of the most serious race riots in the country’s history was in progress, lasting until June 2. The newspapers reported that practically the entire colored residence section of Tulsa was in flames, that shooting was going on and that motor cars and airplanes were being used by white people in the battle.

One of the first steps which the secretary took was to send a telegram to Governor Robertson of Oklahoma, urging him to use the full power of his office to put an end to the reign of violence and terror. Statements were also issued to the New York newspapers warning their readers that a race riot is never caused by one isolated case of assault, and that probably conditions of peonage in the country surrounding Tulsa had brought about a situation of dangerous ill feeling.

These statements received startling confirmation when, on June 2, four refugees from the riot zone appeared at the National Office. The names of the refugees were Lizzie Johnson, Stella Harris, Josie Gatlin and Claude Harris, all from Okmulgee. They had formed part of a group of eight which had left Oklahoma before the riots began. They told terrible stories of the oppression visited upon colored people, said that the practice of peonage was common, and that colored farmers were kept always in debt, the planters taking their crops and giving them only a bare subsistence in return. The refugees said warnings had been distributed weeks and months before the riot, telling colored people they would have to leave Oklahoma before June 1, or suffer the consequences. Cards had been posted outside the doors of colored people’s homes warning them to get out of the state, and a white newspaper of Okmulgee had published a similar warning.

The refugees had left Oklahoma and arrived in New York City possessing practically nothing except the clothes on their backs. Being members of that body they had gone, they said, to the offices of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Marcus Garvey’s organization, where they were told they could not be taken care of, and where, according to their accounts, efforts were made to communicate with Okmulgee to prevent other colored people from coming to New York.

Refused assistance by the Garvey organization, they were brought to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People by Mr. Edward Givens, of 39 West 133d Street, New York City. His rôle was indeed that of the good Samaritan, for he had taken these homeless people under his wing, had given them food, shelter and clothing and had tried to get them work.

A collection was at once taken up for them in the National Office, and in the offices of The Crisis, and the sum of $51.50 was presented to them to tide them over their immediate difficulties. At a meeting of the New York Branch on the same evening an additional contribution was raised for these people. Thereupon the secretary announced in the newspapers that a relief fund was to be established by the Association, and that every cent contributed to it would be applied to relief of the riot victims.

Meanwhile, the stories told by the refugees from the riot zone were sent out to the press and were prominently featured in the most important newspapers, appearing on the first page of the New York World, and being published in the New York Times, the Tribune, the Herald, the Evening Post, the Globe and the Evening World.

The national secretary then took further action. He sent the following telegram to President Warren G. Harding in Washington:

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People feels that an utterance from you at this time on the violence. and reign of terror at Tulsa, Okla., would have an inestimable effect not only upon that situation but upon the whole country.

James Weldon Johnson

President Harding replied through his secretary on June 7 as follows:

Following the receipt of your telegram of June 2, the President, as you will have noticed, made a public expression of his regret and horror at the recent Tulsa tragedy, which reflected his sentiments.

Meanwhile telegrams had been sent to Oklahoma branches telling them that a representative of the National Office was on the way. The fearless temper of the men in the midst of the disturbance is well illustrated by the following telegram which the Boley, Okla., branch sent to the National Office in reply to its telegram. This telegram was received at the National Office on June 3:

Telegram received. Representative will have all moral and financial support demanded. Oklahoma branches and friends loyal and fearless.

C. F. Simmons

At the time of writing, the refugees from Oklahoma are being cared for, and the Association is ready to publish the reports of its investigator as soon as they arrive.