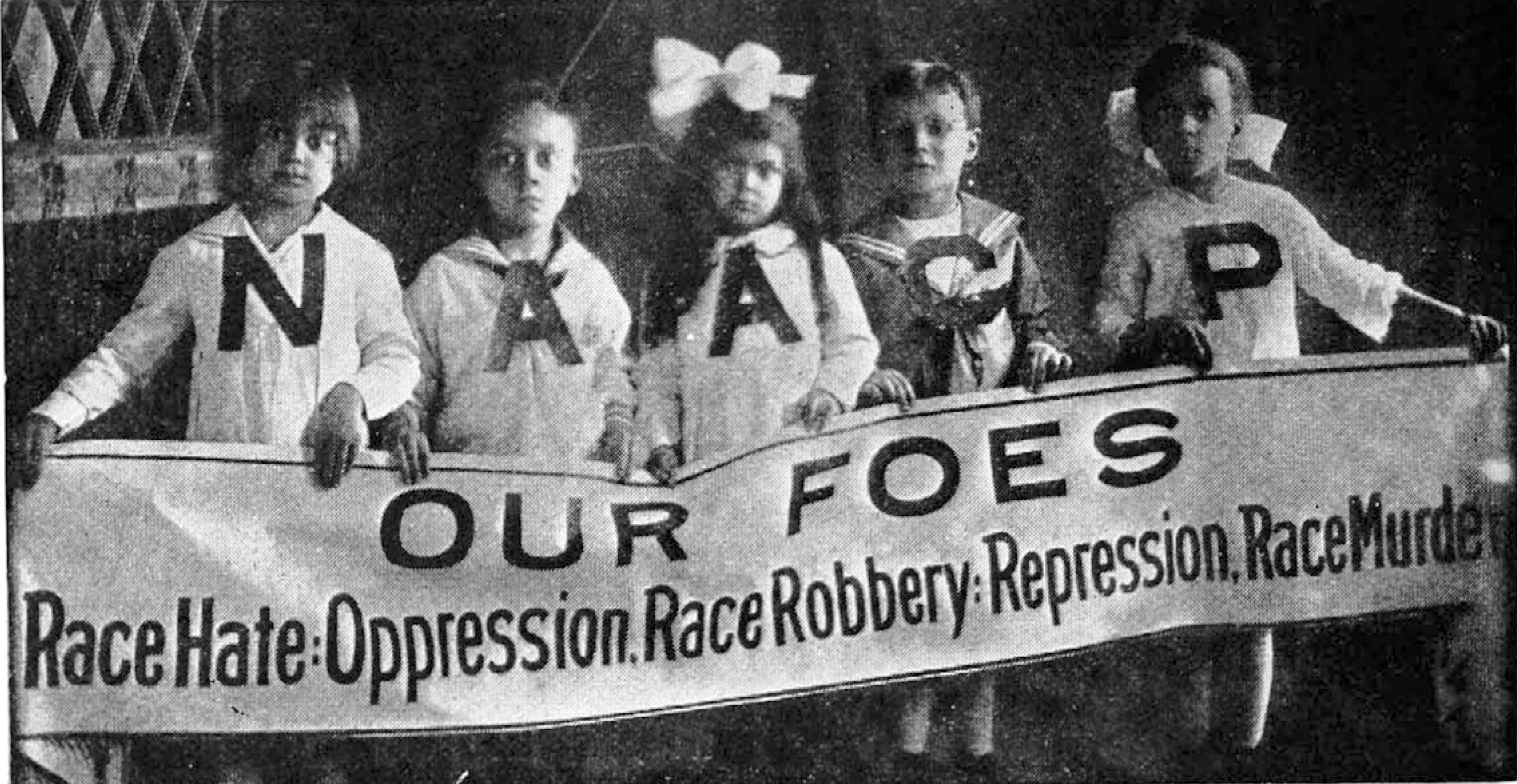

The Burning of Jim Mc Ilherron: An N.A.A.C.P. Investigation

By Walter F. White, Assistant Secretary

The facts given below were secured by Mr. White within the week following the burning of McIlherron in interviews with a number of the citizens of Estill Springs, largely white, including the proprietors of several stores, farmers and others. The account is not a compilation of opinions, but is based upon statements of inhabitants of the town, some of whom were eyewitnesses to the burning. All of the accounts of the burning were given by white people.

The Town

Estill Springs, the scene of the third within nine months of Tennessee’s burnings at the stake, is situated about seventy-four miles from Chattanooga, being midway between that city and Nashville. The town itself has only two hundred inhabitants; with the territory within the radius of a half-mile, about three hundred. Franklin County, in which Estill Springs is located, had a white population of 17,365 and 3,126 colored inhabitants in 1910, according to the census. Estill Springs is not incorporated and, therefore, has no mayor or village officials. It is a small settlement located midway between the larger and more progressive villages of Decherd and Tullahoma, each having about 2,000 inhabitants. Winchester, fifteen miles from Estill Springs, is the county seat.

Estill Springs is made up of a small group of houses and stores gathered about the railway station. The main street is only three blocks long. Its few business establishments are located on one side of this street. There is one bank, the Bank of Estill Springs, purely local in nature; a barber shop, a drug store and five general merchandise stores of the type indigenous to small rural communities in the South. The settlement’s sole butcher left on the day that the investigator reached there, to work in a nitrate factory in a nearby town as the butcher trade of the community was not sufficient to support his shop. Simply stated, Estill Springs is one of thousands of small settlements of its type, poorly located from a geographic and economic standpoint and with little prospect of future growth. Its static condition, naturally, tends to make the minds of its inhabitants narrow and provincial. The people of the surrounding country are farmers and because of the failure of the cotton crop last fall, occasioned by an early frost, corn was the only crop on which they made money. Such of the people as were interviewed were leisurely of manner and slow of speech and comprehension.

Paradoxical as it may seem, in the light of the event which has put Estill Springs on the map in a kind of infamy of fame, the settlement seems to have a strong religious undercurrent. Small as the community is, it has four white churches, two Baptist, one Methodist and one Campbellite. In addition, there are two colored churches, one a Baptist and the other a Methodist, of which latter the Rev. G. W. Lych was pastor. There is a local Red Cross unit among the white women which was planning to inaugurate meetings to knit for the soldiers. In the windows of a number of homes, the emblem of the National Food Conservation Commission was displayed. The son of the proprietor of the only hotel is local agent for the sale of Thrift Stamps. The town purchased its allotment of both the first and second Liberty Loans.

The Cause of the Trouble

About one mile from the railway station of Estill Springs, there lived a Negro by the name of Jim McIlherron. He resided with his mother, several brothers and father, who bears the reputation of being wealthy “for a Negro,” as he owns his own land and is prosperous in a small way. The McIlherrons do not appear to have been popular with the white community. They were known as a family which resented “slights” and “insults” and which did not willingly allow its members to be imposed upon by unfriendly whites. However, there appears to have been no serious trouble between them and their white neighbors up to the time of the street fight which resulted in the shooting for which Jim McIlherron was later burned at the stake. One white woman expressed in a local phrase the opinion of the family when she said that the McIlherron family were “big-buggy niggers,” meaning that they were prosperous enough to have a few articles other than bare necessities, among these being a larger buggy than was common in the section. Most of the whites in the locality, it must be explained, were of the poorer country folk.

Jim McIlherron bore the reputation in Estill Springs of being a “bad sort.” It was gathered from remarks made that this implied that he shared the family characteristic already alluded to of resenting “slights” and “insults.” In other words, he was not what is termed “a good nigger,” which in certain portions of the South means a colored man or woman who is humble and submissive in the presence of white “superiors.”

McIlherron was known to be a fighter and the possessor of an automatic revolver. (Laws against “gun-toting” are observed in the breach, apparently, in this region.) He was, therefore, classed as a dangerous man to bother with. A little over a year before the lynching, he became involved in a fight with his own brother in which the latter was cut with a knife wielded by the former. For this he was arrested by Sheriff John Rose, the sheriff of Franklin County. At the time of this affair, McIlherron threatened to “get” the sheriff if he was ever arrested again by that officer. It is an admitted fact in the community that the sheriff was afraid of McIlherron. Soon after the trouble with his brother, McIlherron went to Indianapolis where he worked in an industrial plant, proceeding later to Detroit. In Detroit he had an attack of rheumatism and was forced to return to his home shortly before the shooting. His having lived in the North tended to increase his disfavor with the white people of the community, as he was credited with having absorbed during his residence there certain ideas of “independence” which were not acceptable to the white citizens of this small rural community.

Sharing popular disfavor with McIlherron was the pastor of the Methodist church in Estill Springs, the Rev. G. W. Lych. He had repeatedly advised the colored people to assert their right to be free from the petty tyranny alleged to have been imposed upon them by the white people, assuring them that they were made of the same clay and were as good as anybody else.

The Shooting

On the afternoon of Friday, February 8, Jim McIlherron went into a store in the town and purchased fifteen cents’ worth of candy. In Estill Springs it had been a habit of an element of young white men to “rock” Negroes in the community—i.e., throwing rocks or other missiles at them to make them run. This had occasioned frequent tilts between the races none of which, however, had previously been serious. McIlherron had been the victim of one of these “rockings” and had declared that if ever they got after him again, somebody was going to get hurt. When the trouble started on February 8, it was about five o’clock in the afternoon, in the gloom of early nightfall. It is probable that the Negro believed that they were after him again. He walked down the street eating this candy, going past Tate & Dickens’ store in front of which he encountered three young white men, Pierce Rogers, Frank Tigert and Jesse Tigert by name. As McIlherron passed them a remark was made by one of the young men about his eating the candy. The others laughed and several more remarks were made. At this the Negro turned and asked if they were talking about him. Words followed, becoming more and more heated, until threats began to be passed between them. One of the young men started into the store whereupon McIlherron, apparently believing, as one of our white informants said, that they were preparing to start a fight, pulled out his gun and started shooting. Six shots were fired, two taking effect in each man. Rogers died in his tracks, Jesse Tigert died about twenty minutes later and Frank Tigert was carried to the office of Dr. O. L. Walker, Estill Springs’ only physician, where he received medical aid. The latter will recover, as his wounds are not serious.

The Man Hunt

Immediately after the shooting, McIlherron, in the attendant excitement, ran down the road leading toward his home. There was no immediate pursuit by the whites. Although everybody knew that he had gone to his home, the white people waited and sent all the way to Winchester, the county seat, some fifteen miles distant, at a cost of sixty dollars, to secure blood-hounds. When these arrived, they succeeded in tracking him only as far as his home, where the scent was lost.

Intense excitement prevailed in the town as news of the shooting spread. In this chaotic state of affairs, no one seemed to know what to do and threats of lynching began to be made. A few of the cooler heads pleaded that the crowd allow the sheriff to handle the entire affair. Knowing of the sheriff’s fear of the Negro, the crowd greeted this suggestion with a derisive shout, and cries of “Lynch the nigger” answered this plea. Plans were laid to form posses to catch McIlherron. Word was sent to Sheriff Rose at Winchester, upon receiving which he immediately left for Estill Springs.

Shouts of “Electrocution is too good for the damned nigger,” “Let’s burn the black——” and others of the sort rose thick and fast. Led by its more radical members, the mob soon worked itself into a frenzy; a posse was formed and set out on the manhunt.

Meanwhile, McIlherron had gone to his home, gathered his few clothes and proceeded to the home of Lych, who aided him in his flight. On two mules they set out in the direction of McMinnville, in an attempt to reach the Tennessee Central Railroad where McIlherron could get a train that would take him to safety. The preacher went a part of the way with McIlherron and then returned to his home in Prairie Springs, a small settlement about twelve miles from Estill Springs. The news soon spread that Rev. Lych had aided McIlherron in his flight and a part of the mob went to Prairie Springs to “get” him for this. Two members came upon him near his home. One of them pointed his gun at the preacher and pulled the trigger. The gun did not go off, and before he could fire again, Lych snatched the gun from his assailant’s hands, broke it and started towards the man with the stock in his hands, when the other man fired a charge into the preacher’s breast, killing him instantly.

The hunt for McIlherron continued throughout Friday night, Saturday, Sunday and Monday, large posses of men scouring the surrounding county for him. Monday night he was located in a barn near Lewer Collins River, just beyond McMinnville. The barn was surrounded and the posse began firing on it. The Negro answered the fire, this state of affairs continuing throughout Monday night. During this time McIlherron succeeded in holding off the crowd, whose numbers were rapidly augmented, when the news spread that the Negro had been located. In the hundred or more men in the posses were Deputy Sheriff S. J. Byars and Policeman J. M. Bain. In the fusillade of bullets poured into the barn, McIlherron was wounded, one eye being shot out. He also received two body wounds, one in the arm and one in the leg. Finally, McIlherron’s ammunition gave out and, weak from the loss of blood, he was forced to surrender when the barn was rushed. When captured, the triumphant members of the mob carried him into McMinnville. The feeling against him was so great that an attempt was made to lynch him in the town of McMinnville, but the citizens of that town refused to allow a lynching in their midst and were able to prevent it from happening. McIlherron was, therefore, placed on Train No. 5, en route to Estill Springs, where he arrived at 6:30 P. M. on Tuesday.

The Crowd

In the meantime, news of the capture spread like wild fire and men, women and children started pouring into the town to await the arrival of the victim. They came from a radius of fifty miles, coming from Coalmont, Winchester, Decherd, Tullahoma, McMinnville and from the country districts. In buggies and automobiles, on foot, on mules, they crowded into the little settlement, until it was estimated that from 1,500 to 2,000 people were in the town. A high state of excitement prevailed as the time for the arrival of the train drew near. Threats of the torture to be inflicted were made on many sides. Boxes, excelsior and other inflammable material were gathered in readiness for the event, and iron bars and pokers were obtained. Most of the crowd were grim and silent, but there were some who laughed and joked in anticipation of the coming event.

Finally, the train drew near. McIlherron was so weak upon arrival, from the loss of blood due to three wounds received in the battle with the posse, that he was unable to stand and had to be carried to the spot selected for his execution. The leaders of the mob decided that he should be lynched on the exact spot where the shooting occurred. He was, therefore, carried to this place where preparations for the funeral pyre were made. The cries of the crowd grew more and more vengeful as the moments passed.

Just as the arrangements had been completed, a few of the braver spirits among the women of the town demanded that the Negro be not burned in the town itself, but be taken out a little way in the country. There were loud objections to this proposal from the now uncontrollable mob. The women insisted, in spite of these objections, and finally it was decided to carry McIlherron across the railroad into a small clump of woods in front of the Campbellite church. This was done and the mob transferred its activities to the new execution ground.

The self-appointed leaders of the mob by this time had great difficulty in restraining the wild fury of the crowd. They were constantly forced to appeal to them not to strike McIlherron or to spit on him, but to allow the affair to be a “perfectly orderly lynching.” The sister of one of the men slain was in the mob and had become frantic in her pleas to the men to let her kill the Negro. She demanded that he be killed immediately, not to allow him to live another moment. It was evident that such a humane thing as instant death would not have appeased the blood-thirst of the mob, in its revengeful mood.

The Torture

On reaching the spot chosen for the burning, McIlherron was chained to a hickory tree. The wood and other inflammable material already collected was saturated with coal oil and piled around his feet. The fire was not lighted at once, as the crowd was determined “to have some fun with the damned nigger” before he died. A fire was built a few feet away and then the fiendish torture began. Bars of iron, about the size of an ordinary poker, were placed in the fire and heated to a red-hot pitch. A member of the mob took one of these and made as if to burn the Negro in the side. McIlherron seized the bar and as it was jerked from his grasp all of the inside of his hand came with it, some of the skin roasting on the hot iron. The awful stench of burning human flesh rose into the air, mingled with the lustful cries of the mob and the curses of the: suffering Negro. Cries of “Burn the damned hound,” “Poke his eyes out,” and others of the kind came in thi « confusion from the mob. Men, women and children, who were too far in the rear, surged forward in an attempt to catch sight of and gloat over the suffering of the Negro.

Now that the first iron had been applied, the leaders began eagerly to torture McIlherron. Men struggled with one another, each vying with his fellow, in attempting to force from the lips of the Negro some sign of weakening. A wide iron bar, redhot, was placed on the right side of his neck. When McIlherron drew his head away, another bar was placed on the left side. This appeared to amuse the crowd immensely and approving shouts arose, as the word was passed back to those in the rear of what was going on. Another rod was heated and, as McIlherron squirmed in agony, thrust through the flesh of his thigh, and a few minutes later another through the calf of his leg. Meanwhile, a larger bar had been heating, and while those of the mob close enough to see shouted in fiendish glee, this was taken and McIlherron was unsexed.

The unspeakable torture had now been going on for about twenty minutes and the Negro was mercifully getting weaker and weaker. The mob seemed to be getting worked up to a higher and higher state of excitement. The leaders racked their brains for newer and more devilish ways of inflicting torture on the helpless victim.

The newspapers stated that McIlherron lost his nerve and cringed before the torture, but the testimony of persons who saw the burning is to the effect that this is untrue. It seems inconceivable that any person could endure the awful torture inflicted, however great his powers of resistance to pain, and not lose his nerve. The statements of onlookers are to the effect that throughout the whole burning Jim McIlherron never cringed and never once begged for mercy. He was evidently able to deny the mob the satisfaction of seeing his nerve broken, although he lived for half an hour after the burning started. Throughout the whole affair he cursed those who tortured him and almost to the last breath derided the attempts of the mob to break his spirit. The only signs of the awful agony that he must have suffered were the involuntary groans that escaped his lips, in spite of his efforts to check them, and the wild look in his eyes as the torture became more and more severe. At one time, he begged his torturers to shoot him, but this request was received with a cry of derision at his vain hope to be put out of his misery. His plea was answered with the remark, “We ain’t half through with you yet, nigger.”

By this time, however, some of the members of the mob had, apparently, become sickened at the sight and urged that the job be finished. Others in the rear of the crowd, who had not been able to see all that took place, objected and pushed forward to take the places of some of those in front. Having succeeded in this, they began to “do their bit” in the execution. Finally, one man poured coal oil on the Negro’s trousers and shoes and lighted the fire around McIlherron’s feet. The flames rose rapidly, soon enveloping him, and in a few minutes McIlherron was dead.

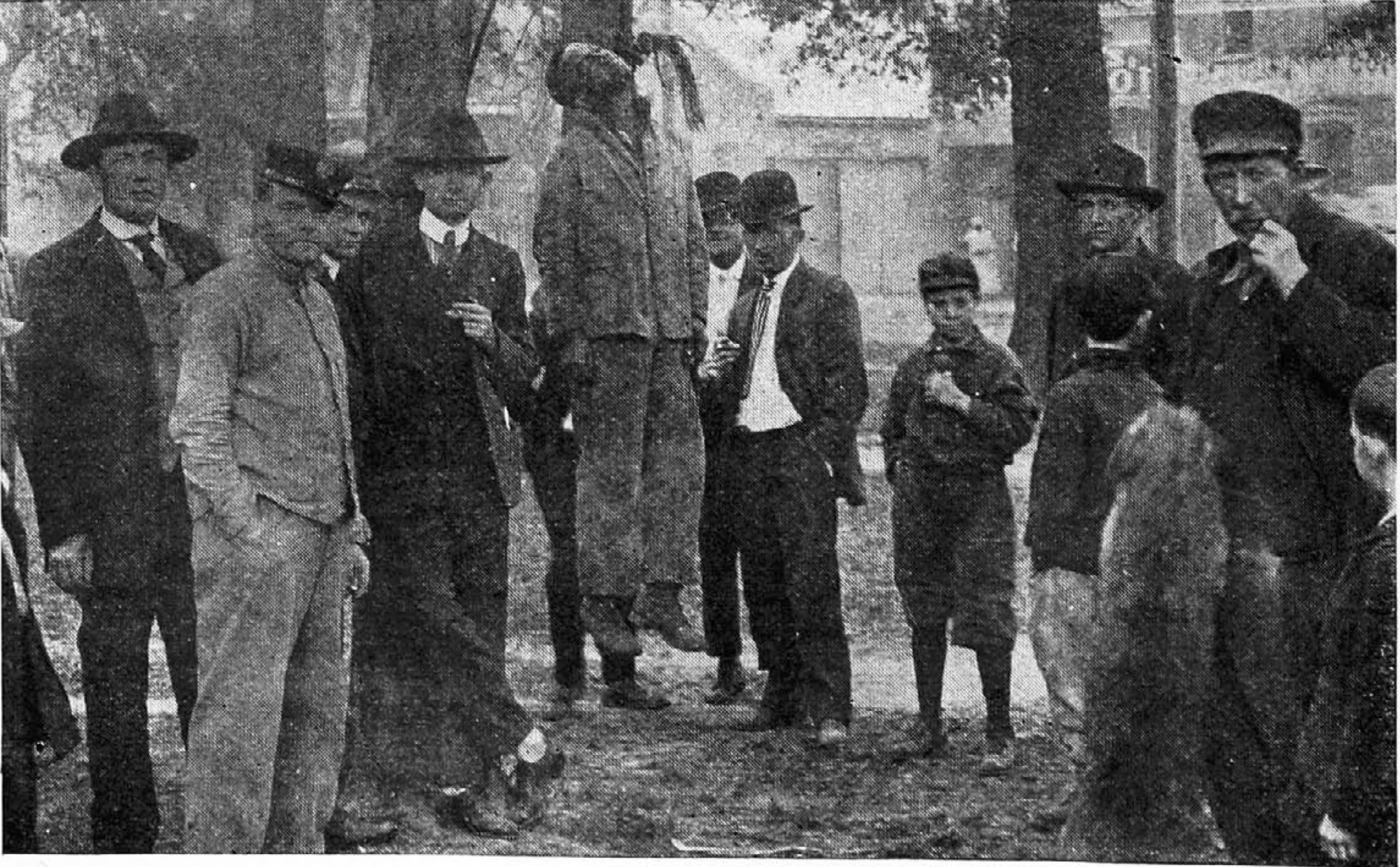

George McNeel, Lynched in Monroe, LA., March 16, 1918.

The Grand Jury Found “No information sufficient to Indict” the lynchers, but this postcard was sold on the streets “to white people” at 25 cents each.